The spy who was shoved into the cold

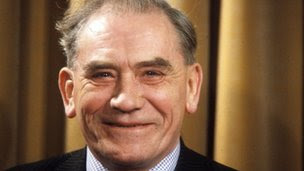

Poor Ray Mawby. The late Conservative M P for Totnes, exposed this week as a sometime spy for communist Czechoslovakia, was a lonely and hollow man, which wasn’t really his fault. Unfortunately, he’d been made into a symbol.

Winston Churchill acclaimed Ray as the first of a “new breed” of Tory: blue collars sporting a blue rosettes. Men like Mawby, working class trade unionists (Ray was, I think, in the Transport and General Workers Union) were the party’s parliamentary future, Churchill declared. They were going to sweep aside the gentlemen of the shires, the old Etonians, the Oxbridge clubmen and lawyers.

I’m not sure if he was the last as well as the first of this new generation, but I certainly never heard of another. And like everyone who gets cast as a symbol, Ray was trapped in the role, hollowed out by it, his own volition paralysed. Other M P’s, of whichever party, who conformed more closely to that rather tedious, Downton Abbey-esque script which British politics (as we are seeing now) is inclined to follow, didn’t know what to make of him. They weren’t easy in his company.

Ray Mawby’s life touched mine just once. I was a barely fledged reporter on The Western Morning News, about a third of the way into my first notebook. It was a Sunday. A man phoned the newsdesk, saying he was the Totnes Conservative party agent. He gave me a report of a speech which he said Ray had made at some event in South Devon in which the M P denounced American imperialism and aggression in Vietnam and called for the withdrawal of all Western troops.

My couple of paragraphs appeared in Monday’s WMN, and at about 10 o’clock the editor called me in. He was quite lenient with me (though after all, between my Imperial typewriter and the street were a copy-taster, the news editor, the chief sub-editor, a sub-editor and a proof reader).

But did I really suppose, the editor asked, that the opinions voiced in my report were those usually espoused by right-wing, Tory members of parliament?

It was a useful lesson in stepping back and thinking, and in checking the facts.

And to be fair, the editor continued, I should have been warned that Mawby was frequently a victim of this kind of imposture. Why? Because socialists saw him as a turncoat: a traitor to the trade union movement and, in the editor’s words, “the man who betrayed his fellow proles by taking the Tory shilling”.

How ironic, then, that he was actually spying at the time for one of the Soviet bloc’s beacons of red revolution and worker solidarity, handing the Czech secret services, inter alia, a floor-plan of the Prime Minister’s office and regular reports about the “peculiarities” (sexual, one imagines) of his fellow Tories in the House of Commons.

Doubly ironic, perhaps, that he wasn’t in espionage for any ideological reason or purpose, but because his controllers had discovered he was in the grip of a gambling compulsion and running out of money. A sucker, then, for blank Czechs (forgive me) and left-wing hoaxers.

Poor Ray Mawby, as I say. Why did he gamble? I guess, because he was lonely. Why was he lonely? Because he was a symbol, a fish out of water, a hollow man and an existential void, and for that reason nobody much liked him. In middle-class, liberal-leaning Totnes he was an oik, all hobnail and worsted, old spice and brylcreem in a milieu of muslin and tie-dye, henna and patchouli. “My dear, have you seen his fingernails?”

I was told that when he was in the constituency, Ray Mawby would spend all the night until closing time in the Conservative Club, approaching no-one, approached by no-one, speaking to no-one, spoken to be no-one, standing alone, drinking whisky, and ceaselessly playing the fruit machine.

In 1983, the oik got deselected by an ungrateful constituency party. He afterwards fetched up on the dole.

His replacement, Anthony Steen, was a proper patrician with a mansion who served until 2009 when he, in turn, got dumped by the locals for taking £87,729 in expenses. He complained that his constituents were envious: “Do you know what this is about? Jealousy,” he said. “I’ve got a very, very large house. Some people say it looks like Balmoral.“

There’s no pleasing those Totnesians, is there?

Winston Churchill acclaimed Ray as the first of a “new breed” of Tory: blue collars sporting a blue rosettes. Men like Mawby, working class trade unionists (Ray was, I think, in the Transport and General Workers Union) were the party’s parliamentary future, Churchill declared. They were going to sweep aside the gentlemen of the shires, the old Etonians, the Oxbridge clubmen and lawyers.

I’m not sure if he was the last as well as the first of this new generation, but I certainly never heard of another. And like everyone who gets cast as a symbol, Ray was trapped in the role, hollowed out by it, his own volition paralysed. Other M P’s, of whichever party, who conformed more closely to that rather tedious, Downton Abbey-esque script which British politics (as we are seeing now) is inclined to follow, didn’t know what to make of him. They weren’t easy in his company.

Ray Mawby’s life touched mine just once. I was a barely fledged reporter on The Western Morning News, about a third of the way into my first notebook. It was a Sunday. A man phoned the newsdesk, saying he was the Totnes Conservative party agent. He gave me a report of a speech which he said Ray had made at some event in South Devon in which the M P denounced American imperialism and aggression in Vietnam and called for the withdrawal of all Western troops.

My couple of paragraphs appeared in Monday’s WMN, and at about 10 o’clock the editor called me in. He was quite lenient with me (though after all, between my Imperial typewriter and the street were a copy-taster, the news editor, the chief sub-editor, a sub-editor and a proof reader).

But did I really suppose, the editor asked, that the opinions voiced in my report were those usually espoused by right-wing, Tory members of parliament?

It was a useful lesson in stepping back and thinking, and in checking the facts.

And to be fair, the editor continued, I should have been warned that Mawby was frequently a victim of this kind of imposture. Why? Because socialists saw him as a turncoat: a traitor to the trade union movement and, in the editor’s words, “the man who betrayed his fellow proles by taking the Tory shilling”.

How ironic, then, that he was actually spying at the time for one of the Soviet bloc’s beacons of red revolution and worker solidarity, handing the Czech secret services, inter alia, a floor-plan of the Prime Minister’s office and regular reports about the “peculiarities” (sexual, one imagines) of his fellow Tories in the House of Commons.

Doubly ironic, perhaps, that he wasn’t in espionage for any ideological reason or purpose, but because his controllers had discovered he was in the grip of a gambling compulsion and running out of money. A sucker, then, for blank Czechs (forgive me) and left-wing hoaxers.

Poor Ray Mawby, as I say. Why did he gamble? I guess, because he was lonely. Why was he lonely? Because he was a symbol, a fish out of water, a hollow man and an existential void, and for that reason nobody much liked him. In middle-class, liberal-leaning Totnes he was an oik, all hobnail and worsted, old spice and brylcreem in a milieu of muslin and tie-dye, henna and patchouli. “My dear, have you seen his fingernails?”

I was told that when he was in the constituency, Ray Mawby would spend all the night until closing time in the Conservative Club, approaching no-one, approached by no-one, speaking to no-one, spoken to be no-one, standing alone, drinking whisky, and ceaselessly playing the fruit machine.

In 1983, the oik got deselected by an ungrateful constituency party. He afterwards fetched up on the dole.

His replacement, Anthony Steen, was a proper patrician with a mansion who served until 2009 when he, in turn, got dumped by the locals for taking £87,729 in expenses. He complained that his constituents were envious: “Do you know what this is about? Jealousy,” he said. “I’ve got a very, very large house. Some people say it looks like Balmoral.“

There’s no pleasing those Totnesians, is there?

Comments

Post a Comment