Christmas with Christina and John

The shade of John Milton, channelled through his statue in a side-aisle and his bust by the bell-tower, was listening in St Giles Church, Cripplegate, as my daughter and her school-fellows sang carols and madrigals this week for Christmas.

“Earth stood hard as iron, water like a stone; snow had fallen, snow on snow, snow on snow.” While I write this, the snow still falls, and the king’s head flowerpot on our garden wall, which in summer is crowned with red geraniums, now wears a mitre of snow.

“In the bleak midwinter,” particularly when sung by sweet trebles and melancholy altos, is the carol most likely to moisten my eyes. It was written by Christina Rossetti, who was a child of December, born on the fifth in 1839 and dying on the 29th in 1894, and who lived, as we do, in Camden.

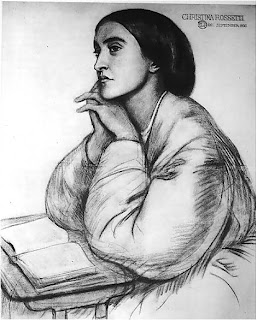

It was only when I found this pencil portrait of her, drawn by her brother, the better-known artist and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti, that I realised what an archetype she was of the pre-Raphaelite female, later more famously realised through the exquisite young lineaments of Jane Morris and Elizabeth Siddal.

Of the second of these women, muse, lover and briefly wife of her brother, Christina wrote a sonnet called “In an artist’s studio”:

One face looks out from all his canvases,

One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans:

We found her hidden just behind those screens,

That mirror gave back all her loveliness.

A queen in opal or in ruby dress,

A nameless girl in freshest summer-green,

A saint, an angel – every canvas means

The same one meaning, neither more nor less.

He feeds upon her face by day and night,

And she with true kind eyes looks back on him,

Fair as the moon and joyful as the light:

Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim;

Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright;

Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.

What sent me back to read this again, sharpening its sestet’s twist and turning the whole into a different poem, was the discovery that it was written in 1890. Which is eight years after DGR died, and nearly thirty years after Siddal had killed herself with an overdose, either suicidal or accidental, of the liquid opium to which she’d become addicted, and which must have wrecked her beauty. In one of those strange but glorious eidetic moments I am lifted out of my world and plonked in front of an HD, 3D film of Christina, ageing, balding, fat, remembering (I think) her first visit to Dante’s studio (cold, damp, musty) just after his death. That vivid, Browning-esque line – we found her hidden just behind those screens – such a simple stage direction; that is the catalyst; that’s what transports me there.

I set this down as a debating point against the purists who argue that knowledge of the life adds nothing to appreciation of the work. Seen from the perspective of 1890, when Christina was in decay and just four years short of her own death, “In an artist’s studio” is a profound, piercing and deliberately ambiguous verse drama.

Christina was ferociously – some would say destructivley – religious. Two suitors (near lovers, I suspect) got turned away, one for converting to Catholicism, another because his skimmed beliefs were incompatible with her full-fat Protestantism. She died a spinster.

According to a biographer, “Christina gave up chess because she found she enjoyed winning; pasted paper strips over the antireligious parts of Swinburne's “Atalanta in Calydon” (which allowed her to enjoy the poem very much); objected to nudity in painting, especially if the artist was a woman; and refused even to go see Wagner's Parsifal, because it celebrated a pagan mythology.”

And yet, paradoxically, her verses are sensuously alive to the joys of love and the bitterness of loss. As another of her biographers noted, “her pious scrupulousness seems at odds with the heartfelt emotion expressed in her poetry”:

Downstairs I laugh, I sport and jest with all:

But in my solitary room above

I turn my face in silence to the wall;

My heart is breaking for a little love.

Though winter frosts are done,

And birds pair every one,

And leaves peep out, for springtide is begun.

I feel no spring, while spring is wellnigh blown,

I find no nest, while nests are in the grove:

Woe’s me for mine own heart that dwells alone,

My heart that breaketh for a little love.

While golden in the sun

Rivulets rise and run,

While lilies bud, for springtime is begun.

All love, are loved, save only I; their hearts

Beat warm with love and joy, beat full thereof:

They cannot guess, who play the pleasant parts,

My heart is breaking for a little love.

While beehives wake and whirr,

And rabbit thins his fur,

In living spring that sets the world astir.

Am I alone in hearing the ghost of the word "grave" haunting "grove" in the second verse?

During her forties, Christina’s pre-Raphaelite beauty was blasted by a disfiguring illness:

I turn from you my cheeks and eyes,

My hair which you shall see no more –

Alas for joy that went before,

For joy that dies, for love that dies...

If now you saw me you would say:

Where is the face I used to love?

And I would answer: Gone before;

It tarries veiled in paradise

When I re-read those lines this week, it struck me that they might be intended to conjure just a little resonance of – could almost be in distant conversation with – John Milton’s great sonnet “Methought I saw my late espousèd saint,” in which the blind poet describes a dream of his dead wife:

And such as yet once more I trust to have

Full sight of her in Heav'n without restraint,

Came vested all in white, pure as her mind:

Her face was veil'd, yet to my fancied sight

Love, sweetness, goodness in her person shin'd

So clear, as in no face with more delight.

But O as to embrace me she enclin'd

I wak'd, she fled, and day brought back my night.

And I thought I found more dialogue with Milton in Christina’s “Echo”:

Come to me in the silence of the night;

Come in the speaking silence of a dream:

Come with soft rounded cheeks and eyes as bright

As sunlight on a stream;

Come back in tears,

O memory, hope, love of finished years.

Oh dream how sweet, too sweet, too bitter sweet,

Whose wakening should have been in Paradise,

Where souls brimfull of love abide and meet;

Where thirsting longing eyes

Watch the slow door

That opening, letting in, lets out no more.

Yet come to me in dreams, that I may live

My very life again though cold in death:

Come back to me in dreams, that I may give

Pulse for pulse, breath for breath:

Speak low, lean low,

As long ago my love, how long ago!

Such tentative connections, fruits plucked as I wander through the great whispering gallery of poetry and poets, are a kind of consolation at the end of a rather melancholy year. Let’s hope our midwinters aren’t too bleak. Happy Christmas – raise a glass, if you wish, to Christina and John. Both would approve, I think, as long as it’s only the one. Or possibly, one for each.

Comments

Post a Comment